It is never easy to do everything by yourself. Since the beginning of time, humans truly understood, often with a huge cost, that their true power lies not in conflicts but in collaboration. Programming paradigm is also not quite different. For an application to live long, it must figure out the dependencies and try to look for ways to delegate others to serve the dependencies it needs. Not only this can solve its own problem efficiently, but it can also, in turn, help other programs by presenting itself as their dependency.

Dependency Injection is a crucial application design pattern for almost all the frameworks out there to create reusable, manageable and testable code. Today let’s try to simplify Dependency Injection, which is a subset of Inversion of Control principle, with TypeScript.

But first, let us set the table straight. If you have noticed any top class restaurant’s kitchen operation then you will find this article’s motivation a bit similar. In a restaurant, each Station Chef is responsible for running a specific section of the kitchen and they are being managed directly by the Head Chef or by the second-in-command Sous Chef. Station chefs (for e.g. butcher chef, fish chef, grill chef) can be in charge of different things respectively.

Whenever one order comes to the kitchen via a Caller, the Sous Chef simply doesn’t start preparing it all by himself. He runs down what are the things he needs to deliver, and start instructing them accordingly to each Station Chef. He expects they would handover their prepared items on a common table, where the entire dish can then be prepared or garnished for serving.

This is an important takeaway that we will soon find out in this article but before that here is a rundown of the topics you will get introduced in this article.

- Dependency Injection

- Dependency Inversion Principle

- Inversion of Control

- Inversion of Control Container

- TypeScript Interfaces

- Decorator Functions

- Reflection APIs

- TypeScript IoC

Problem Statement

Let’s present a problem we are going to recreate and solve, called “Pizza making chronicles”.

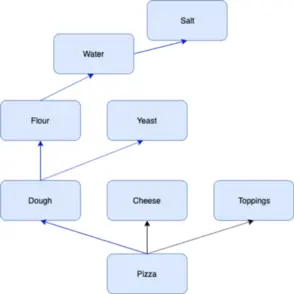

Pizza making got several dependencies to start with. Ignoring cheese and toppings (even sauce) for simplicity, we can see that a pizza needs dough and dough needs flour and yeast. Flour and Yeast needs water. Water needs salt. Here is a directed graph diagram that roughly shows those dependencies:

Dependency Injection

Dependency injection is a fancy phrase that essentially means this: class dependencies are “injected” into the class via the constructor or, in some cases, “setter” methods. - From Laravel.

A pizza needs dough to start with. Let’s see how does that look in a typical code base.

export class Pizza {

private dough;

public constructor() {

this.dough = new Dough();

}

}

Soon we figure out that this Dough class is also required for making bread, so its redundant to allow both Pizza and Bread to be in charge of Dough all by themselves. So let’s delegate the creation of Dough to someone else. We inject the dependency Dough in Pizza constructor, an example of the most famous constructor based Dependency Injection.

export class Pizza {

private dough;

public constructor(dough: DoughEntity) {

this.dough = dough;

}

}

However, we passed a concrete implementation of Dough in Pizza, called DoughEntity. But customers might order different types of dough for different pizzas later.

Dependency Inversion Principle

“..DIP says that our classes should depend upon abstractions, not on concrete details.” — Robert C. Martin

Since dependency implementations can be swapped easily as they are injected during runtime, we should rather inject an interface, like IDough so that we can later swap it with any concrete implementation of IDough, i.e DoughEntity like SourdoughDough, BriocheDough, ChallahDough, FocacciaDough etc.

export class Pizza {

private dough;

public constructor(dough: IDough) {

this.dough = dough;

}

}

With dependency injections, we ensured that the chef making pizza can’t make his own dough, and with dependency inversion principle we ensured that different kinds of dough can now be used for making pizza. Same goes for the dough maker. The dough maker doesn’t decide which flour and what kind of flour he will use rather it is handed to him by someone else in the charge of the pantry. There is a slight problem with this pattern in applications. This might lead to a nested and complicated dependency graph because we keep manually initiate the dependencies and pass them up to the ones who need it. So what to do?

Inversion of Control

In software engineering, inversion of control (IoC) is a programming principle. IoC inverts the flow of control as compared to traditional control flow. In IoC, custom-written portions of a computer program receive the flow of control from a generic framework. - From Wiki

Dependency Injection so far looked like this: The Caller needs a pizza and announces it in the kitchen. The Pizza Chef doesn’t make the dough himself, he asks for it from the dough maker. But imagine the dough maker now says, “Don’t ask me for the dough, I will keep my dough on a table when I am done myself.” There is a Hollywood Principle, which states:

“Don’t Call Us, We’ll Call You”

This is what inversion of control looks like. The Pizza Chef doesn’t directly gets the dough from the dough maker, rather he will get it from an external place without him having the knowledge of who added it there or when was it added.

Inversion of Control Container

So finally we have a kitchen table which contains the prepared items. The pizza chef takes everything from there when he needs it and starts making pizza. A programming container also behaves as such, which typically bind interfaces to implementations and serves them as dependencies when someone needs it. It will look something like this in the code:

const pizzaContainer = new Container();

pizzaContainer.bind<IDough>(IDough).to(DoughEntity);

pizzaContainer.bind<IFlour>(IFlour).to(FlourEntity);

Now let’s code the talk using TypeScript. The demo code is a Node.js application build using Express framework. We will be using InversifyJS, an IoC container for TypeScript, in this project. Here are the dependencies used:

"dependencies": {

"@types/express": "^4.17.1",

"express": "^4.17.1",

"inversify": "^5.0.1",

"reflect-metadata": "^0.1.13",

"tslint": "^5.20.0",

"typescript": "^3.6.3"

}

I used lightweight InversifyJS to simply demonstrate how containers work in applications, and then it will be easier for us to understand how frameworks like Angular or Laravel use DI and IoCs. You can check out the entire repository here: Saad-Amjad/inversify-di-doc.

TypeScript Interfaces

Let us create an interface called Dough. I don’t like using IDough naming, so would name dough as Dough for the rest of the code.

export interface Dough {

getFlour(): Flour;

getYeast(): Yeast;

}

We usually want to code using interfaces so that we have better consistency across classes, but in the generated JavaScript, we do not have any references for it. It is simply non-existent. So how can we use Dependency Injection in TypeScript?

Decorator Functions

Frameworks like Angular and NestJS use decorators to tell their own DI mechanism what are the dependencies other classes require and and how to initialise them. Those decorator functions basically add metadata to our classes. The metadata are used to gain information about what dependencies it needs during runtime and thus helps in resolving them. In Inversify, whenever a class (it will always have @injectable decorators on them) have a dependency on an interface, we use the @inject decorator to define an identifier for the interface that will be available at runtime.

Reflection APIs

Reflection allows inspection and modification of a code base, including its own. Unlike JavaScript, TypeScript does support experimental reflection features, though few in number. Using metadata reflection API we can standardize how we achieve details of unknown objects during runtime.

For the class Pizza, when DoughEntity dependency is called, the Injectable Decorator adds a metadata entry for the property using the Reflect.metadata function from the reflect-metadata library, which gives us an array of dependencies that the class requires. It under the hood presents us with the right information about DoughEntity being a dependency for Pizza.

Here is a simplified example of the metadata generated when we pass a concrete implementation. You can find this behaviour in Node.js frameworks like NestJS, and its decorator usage.

const metadata = Reflect.getMetadata("design: paramtypes", Pizza);

// metadata = [DoughEntity]

We can see that the metadata points to exact DoughEntity. But what if we injected Dough interface?

const metadata = Reflect.getMetadata("design: paramtypes", Pizza);

// metadata = [Object]

When the code transpiles to JavaScript, we get metadata as an Object, with no way for us to say which specific object it is. We need to do something to uniquely identify them so that during runtime the proper class is resolved.

In our demo code after having coded in the interfaces, we type-hint our real classes instead of interfaces. We use Symbol to allow identification of Dough interface with “Dough”.

//symbols as identifiers but you can also use classes and or string literals.

const TYPES = {

Dough: Symbol.for("Dough"),

Flour: Symbol.for("Flour"),

Salt: Symbol.for("Salt"),

Yeast: Symbol.for("Yeast"),

Water: Symbol.for("Water"),

};

export { TYPES };

Let’s create a concrete implementation of Dough now and call it DoughEntity. Here you can see, we mentioned the class as injectable using @injectable decorator, and passed in interfaces in the constructor with @inject decorator so to define the identifiers.

import { injectable, inject } from "inversify";

import { Dough } from "../interfaces/dough.interface";

import { Flour } from "../interfaces/flour.interface";

import { Yeast } from "../interfaces/yeast.interface";

import { TYPES } from "../types/types";

@injectable()

export class DoughEntity implements Dough {

public flour: Flour;

public yeast: Yeast;

public constructor(

@inject(TYPES.Flour) flour: Flour,

@inject(TYPES.Yeast) yeast: Yeast

) {

console.log("Dough class initiated");

this.flour = flour;

this.yeast = yeast;

}

public getFlour(): Flour {

return this.flour;

}

public getYeast(): Yeast {

return this.yeast;

}

}

Now we create a container that binds the interfaces to their implementations such that if Dough types are called, we get concrete implementation of DoughEntity.

const pizzaContainer = new Container();

// pizzaContainer.bind<>().to();

pizzaContainer.bind<Dough>(TYPES.Dough).to(DoughEntity);

pizzaContainer.bind<Flour>(TYPES.Flour).to(FlourEntity);

pizzaContainer.bind<Salt>(TYPES.Salt).to(SaltEntity);

pizzaContainer.bind<Water>(TYPES.Water).to(WaterEntity);

pizzaContainer.bind<Yeast>(TYPES.Yeast).to(YeastEntity);

export { pizzaContainer };

We create the Pizza class as following:

import { injectable, inject } from "inversify";

import "reflect-metadata";

import { Dough } from "./interfaces/dough.interface";

import { TYPES } from "./types/types";

@injectable()

export class Pizza {

public dough;

public constructor(@inject(TYPES.Dough) dough: Dough) {

this.dough = dough;

}

}

Before we do the rest of the code, here is a peek into the future for better understanding. Since we are using decorators and reflection API, if we look at the generated JavaScript code of pizza.class.ts by setting “emitDecoratorMetadata”: true in tsconfig.json, we could see that the Object we get in metadata will be of type Types.Dough.

Pizza = __decorate(

[

inversify_1.injectable(),

__param(0, inversify_1.inject(types_1.TYPES.Dough)),

__metadata("design:paramtypes", [Object]),

],

Pizza

);

And the generated JavaScript code of dough.entity.ts would look like this, where param orders tell us about DoughEntity dependencies:

DoughEntity = __decorate(

[

inversify_1.injectable(),

__param(0, inversify_1.inject(types_1.TYPES.Flour)),

__param(1, inversify_1.inject(types_1.TYPES.Yeast)),

__metadata("design:paramtypes", [Object, Object]),

],

DoughEntity

);

It surely seems that the decorators and reflection API have done its part in figuring out the dependency. And now the moment of truth, let’s resolve a dependency here in the main.ts file and see it in action.

import express from "express";

import { Pizza } from "./pizza.class";

import { pizzaContainer } from "./inversify.config";

const pizza: Pizza = pizzaContainer.resolve<Pizza>(Pizza);

If we run the application and open the console, we can see the following output telling us the Dependency Injection worked using the IoC container.

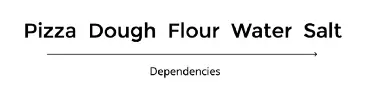

Salt gets initiated first. Water, Flour, Yeast and finally Dough classes were successfully resolved and finally got injected into the Pizza class.

Salt class initiated

Water class initiated

Flour class initiated

Salt class initiated

Water class initiated

Yeast class initiated

Dough class initiated

Pizza class initiated

Conclusion

There is a reason why good kitchens operate similar to this. A real chef can vouch about it more than me for sure. They can truly deliver the best when each of the chefs has singular, separate responsibilities, each knowing exactly what, where and when to contribute in making a perfect dish for the restaurant-goers, with someone managing it, who is however not directly being involved in any of the process details. I am really impressed with the DIs and IoCs of Laravel, Angular and NestJS. It has really made both the backend and frontend code much more manageable, reusable and testable with time. The key concepts are the same in all the frameworks and are rightly so. I hope this simplifies how to handle dependencies in the future.

Happy coding folks!

References/Further Readings:

Inversion of Control Containers and the Dependency Injection pattern

Article Photo by Fabrizio Magoni